Oeke Hoogendijk Has Made a True Art-Thriller With My Rembrandt

In My Rembrandt, documentary filmmaker Oeke Hoogendijk portrays the owners of a painting by the Dutch Old Master. She orchestrates their story into a thrilling detective about the hunt for an unknown Rembrandt. But the most beautiful part is that Hoogendijk also focuses on the absurdity of this story.

Spoiler alert! For anyone who hasn’t seen My Rembrandt: this article contains information about twists and surprising elements that might influence the enjoyment of watching it.

The Amsterdam-based art dealer Jan Six Jnr. just can’t get over it. ‘It’s so blatantly obvious!’ The Portrait of a Gentleman, which is attributed to Rembrandt’s circle in the Christie’s catalogue, is by the master himself. There is no doubt, according to the young heir of the well-known aristocratic family from Amsterdam, who grew up in a stately mansion on the river Amstel. He shows his find to his father, Jan Six Sr., who focuses on the image in the catalogue, ‘we only see it because you’re telling us.’ He willingly allows himself to be enlightened by his son, who is an art historian. Six Jnr. traces his finger across a detailed photo of the canvas whilst he lectures about the composition of the shadow in the face, and ‘Van Dijck’s S-shadow, always over the eyes with Rembrandt’.

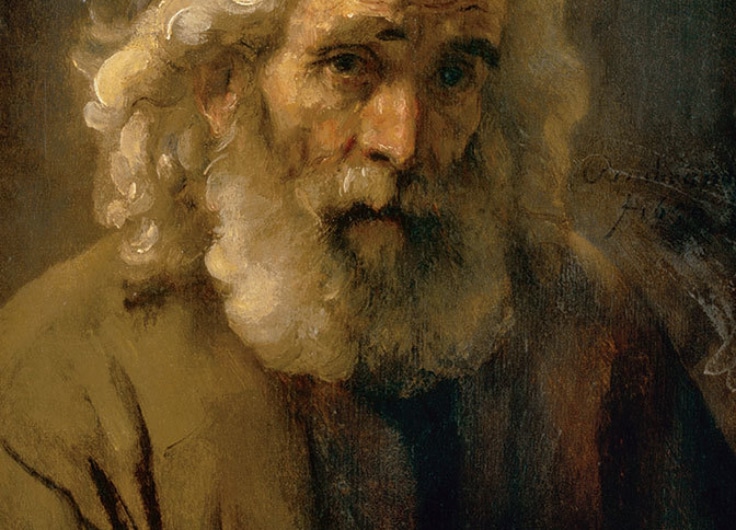

Art dealer Jan Six XI and Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Gentleman (ca. 1634)

Art dealer Jan Six XI and Rembrandt’s Portrait of a Gentleman (ca. 1634)Still from the documentary 'My Rembrandt'

‘Look’, says Jnr. – the 11th Jan Six in a row – turning himself to the wall behind him as proof. Hanging on the wall is the portrait that Rembrandt painted of their forefather, Jan Six I. Both of his eyes, however, disappear largely into the shadow of his hat. But even before Sr. can bring up the point, Jnr. dismisses it as if it were completely irrelevant, claiming that ‘in this case it works differently, because the face is different.’

Instinctive Inspiration

This scene from My Rembrandt, Oeke Hoogendijk’s new film (also known for her 2014 The New Rijksmuseum), is not just exciting and entertaining, but tells us a great deal about the documentary’s main protagonist, his quest, bravura and perspective. Although the young Six is far from the only person portrayed by Hoogendijk in her documentary about owners of Rembrandt portraits, he is the focus. Hoogendijk explains why in an interview with the VPRO: ‘I often find films about art educational, like lectures are. The content is interesting, but the form is not very exciting. I thought: surely you can make a film about Rembrandt that’s a little more like a thriller? An art-thriller. That was the ambition.’

In this thriller, Jan Six Jr. plays the role of Sherlock Holmes with a specialism in art history: an academic detective expertly at work in the land of the Dutch masters, searching for unknown Rembrandts. For instance, when his father fantasises about how a painting could have come into existence, his beloved son casts aside this speculative claptrap. That is just emotional blather, unfounded and unproven, and has nothing to do with science or seeking truth.

Oekje Hoogendijk

Oekje Hoogendijk© Annaleen Louwes

With her discreet but sharply observant camera, Hoogendijk appears to satisfy herself with the role of Holmes’ assistant Watson, the right-hand man that accompanies his brilliant master on their adventures, full of the necessary wonderment. Hoogendijk shows us how Six’s trained eye falls on an apparently unimportant detail, and how it turns out to provide an important clue.

In the case of the first Rembrandt painting that Six discovered, Let The Little Children Come To Me, this clue was a half-hidden self-portrait of a young Rembrandt in the background of a partly overpainted group scene. This put Six on the trail of the famous ‘culprit.’ With the second, Portrait Of A Gentleman, it was the painting’s use of shadow that stood out. Just like Hoogendijk, we watch in fascination as the connoisseur unlocks the secrets of a canvas for us.

Like the real Holmes, Six combines scientific methods such as paint and canvas research and infrared scanning, with more subjective ‘characteristics’ and ‘profiles’ from art science to illustrate what does and doesn’t fit stylistically within the Rembrandt oeuvre.

Rembrandt expert Ernst van de Wetering looking at Portrait of a Gentleman

Rembrandt expert Ernst van de Wetering looking at Portrait of a GentlemanStill from the documentary 'My Rembrandt'

To close the gap between knowledge and belief he calls in Rembrandt specialist Ernst van de Wetering as an independent expert but van de Wetering initially arrives at a different conclusion to Six. He begins to U-turn on this however, when he becomes aware of, and more familiar with the odd one out, and after developing a suitable theory following the discovery of a seam in the canvas. The theory of which Six was convinced from the beginning gains approval – this corpse, or in other words, the newly found painting, could indeed really be Rembrandt’s work.

Playing Dirty?

Portrait of Jan Six by Rembrandt, 1654

Portrait of Jan Six by Rembrandt, 1654© Rijksmuseum Amsterdam/Six Collection

The real intrigue starts to unfold when art dealer Sander Bijl accuses his colleague Six of foul play during the acquisition of the Portrait of a Gentleman in London – a row which also hit Hoogendijk like a ton of bricks. Something which had been simmering away in the background suddenly becomes blatantly obvious – Six Jnr. is no objective detective, he’s a dealer with vested interests. Yes, he wants to prove the murder, but he only has one perpetrator in mind. In criminal law, this well-known and objectionable phenomenon is known as tunnel vision. Something considered a mortal sin among truth-seekers, as it falsely or sometimes deliberately neglects or overrides the exculpatory evidence. The question isn’t ‘who is the perpetrator’, it is instead ‘whether Rembrandt could have been the perpetrator’.

Under these circumstances, Detective Holmes as well as the independent expert, fade from enthusiastic guides into players with a motive. When their motives are revealed, Hoogendijk, initially the docile Watson, turns out to have the sharpest and most independent eye. But the best part is that unlike Six, who points at what we should see, she simply gives us clues on how to piece together the bigger picture, from which we can draw our own theories. After all, why are these men staring so blindly at that one perpetrator?

The beauty of Hoogendijk’s observations, is that she considers the absurdity of the story from the very beginning

The beauty of Hoogendijk’s observations, is that she considers the absurdity of the story from the very beginning. Where the tension initially seems to reside in the possible discovery of a new Rembrandt, it actually lies in the contradictions, the doubts, and not to forget, the vested interests. This creates ambiguity and as such makes it exciting. Whoever thought they were getting a traditional detective story, actually has to follow Hoogendijk’s clues themselves.

Human Imperfection

She leaves the riot between Six and Bijl for what it is, and remains loyal to sketching the broader picture of Rembrandt owners. It is in this way that Six Jnr.’s story makes up only one small part of this much bigger narrative, which explores far more than the hunt for this one possible Rembrandt painting. And that fits in with a tradition of everyday crime-detective stories, which are not so much focused on the neat resolution of that one ‘perfect’ murder, but in which the detective’s quest sooner symbolises a less perfect, more human system in which he may or may not function. My Rembrandt is less about the old master himself, and more about what his work does to the (potential) owners of it. In detective-speak, you could even say Rembrandt functions as a kind of red herring – a kind of distraction from what this art-thriller is really about.

Rembrandt functions as a kind of red herring - a kind of distraction from what this art-thriller is really about

This characterisation of Rembrandt does of course sell him too short, because he as the master with an eye for human imperfection, fits into this story in a way that no other could. Not only does Hoogendijk portray these Rembrandt owners in all their imperfect beauty, the Rembrandt-esque is also evident from the bonds that these owners have with the paintings they possess. Like the French baron Eric de Rothschild who used to wake up with the pendant portraits of Maerten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit on either side of his bed. Or the Scottish Duke of Buccleuch, who lives in his castle together with An Old Woman Reading as if she were one of the family. And then there’s the American businessman Thomas Kaplan, whose alias is ‘the vacuum’, who buys up all of the Rembrandts that come onto the market as if they were company acquisitions. He then presents these trophies like love conquests – he even claims to have kissed the lips of the subject in one painting, which he as the owner is the only person permitted to take into his arms.

Jan Six X in front of the painting of his forefather, Jan Six I.

Jan Six X in front of the painting of his forefather, Jan Six I.Still from the documentary 'My Rembrandt'

A vast love for the work springs from all of these stories, but above all an admiration of the old master whose status radiates through them and how they relate to his work. Hoogendijk comments on the overarching theme of her documentary, ‘Someone said you could see it as the seven deadly sins. All of the characteristics, from vanity to greed, are in there. But also the love of beauty and all the facets that art encompasses.’

Frayed Edges

In any case, that is Hoogendijk’s merit – in an unusual, elite arena filled with internationally acclaimed museums, dignitaries, old and new money – with a light touch, she is able to paint such obvious humanity in all its imperfect beauty. It is no coincidence that, following the example of the Dutch master, she also allows the frayed edges to be filmed, which makes the glamour appear very rugged and real. She films the butler who welcomes the filmmakers in a chic Parisian living room filled with artwork in the run up to the interview with Baron de Rothschild. She films the little dog pottering around, which in terms of its spontaneity, is in no way inferior to the little girl painted amongst the gunmen of the Night Watch. While Hoogendijk sets up her camera, she films father Six as he gives her orders like the captain of ship, as to how she should frame him in her shot. She films in the kitchen, looks over shoulders and from behind picture frames, because the most telling things often happen in the wings.

American billionaire businessman Thomas Kaplan has the world’s largest private collection of Rembrandts.

American billionaire businessman Thomas Kaplan has the world’s largest private collection of Rembrandts.If anything is clear in Hoogendijk’s portrayal it is that things aren’t obvious at first glance and that a portrait asks to be studied in detail. Studied with a sharp, practiced eye, which is open to seeing everything, even when it doesn’t necessarily fit the preconceived picture. An eye that is alert, especially during the moments when no-one is posing. What can then be seen isn’t one-sided and requires further interpretation – an area of tension where instinct might well be the leading principle.